Out of the Lab: No More Disappearing Balls in Baseball Night Games

2018/07/25 Toshiba Clip Team

When baseballs vanish in stadiums, blame the LED lights

Sport stadiums everywhere are replacing high-intensity discharge (HID) floodlights with light-emitting diodes (LEDs). It’s the obvious way to go, as LEDs consume less power and have long lives. However, it seems there is a problem, one that has hit baseball: high flying balls vanish into the night, and LED lighting has even been blamed for players missing catches in the field.

Naturally enough, this complaint caught the attention of researchers who study and develop LED lighting. Was this a real problem? Could losing sight of the ball against floodlights really be due to the LEDs? These questions soon attracted attention at Toshiba Lighting & Technology Corporation, and inspired Hirokuni Higashi, a member of the Lighting Engineering Group, Toshiba Lighting & Technology Corporation, to conduct a series of field and laboratory experiments to explore the phenomenon and develop better sports lighting for players.

Hirokuni Higashi, specialist in Lighting Engineering Group, Toshiba Lighting & Technology Corporation explains his concerns.

A veteran of many years of researching lighting glare, Higashi was motivated by the thought that, “Blaming LED lights for losing sight of balls would just raise unnecessary, groundless concerns among people considering adopting LED lighting.” In his opinion, “This phenomenon is all about the luminance of the lights, rather than whether the lights are LEDs or not. I thought that we could explain the phenomenon scientifically and come up with a solution.”

The first step he took was to visit a stadium to inspect the lighting set-up. There were several lighting towers, each decked with an array of floodlights. As Higashi explains, “A bank of floodlights creates high intensity luminance that can affect human vision.”

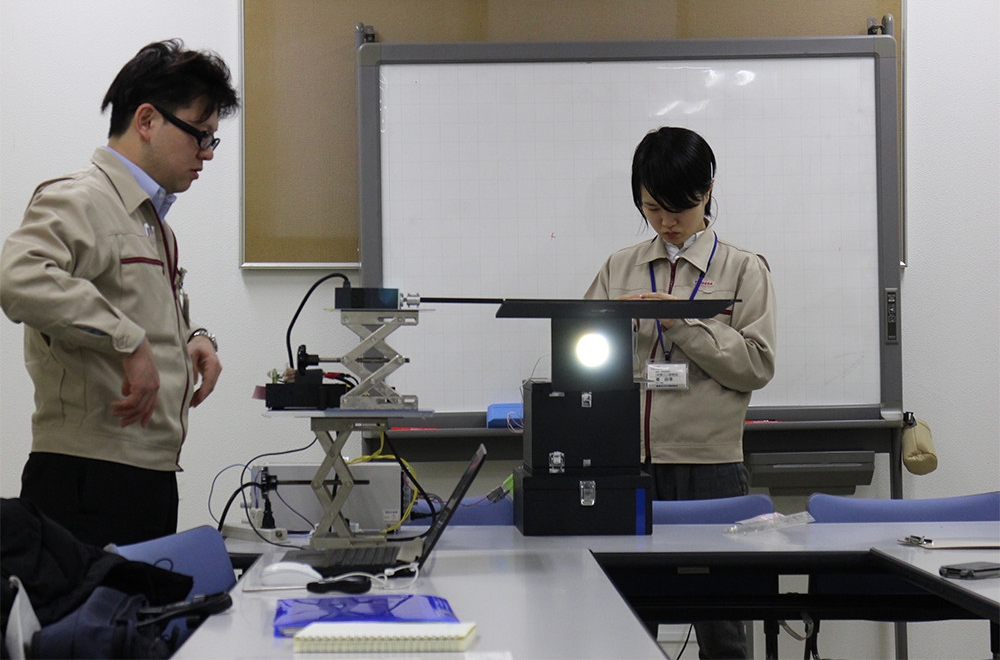

Convinced he had found the cause of the phenomenon, he headed back to the lab, and with the support of new colleague, Yuki Hata, started to design experiments to explore what he called “ball disappearing phenomenon.”

Seeing is believing

Experiments to replicate the problem were held at night in a stadium. They were really helped by the assistance of five members of Toshiba’s baseball team, all with at least ten years of playing experience and all comfortable playing night games.

“Getting the stadium at the time the players were available was the first hurdle,” recalls Higashi. “We had to get ready, conduct the experiment and clean up in the two hours the stadium was made available to us.” Higashi looks back the day of the experiment, “rain was forecast for the day, and I remember nervously eying the rain radar on my smartphone on the train to the ground.”

Members of Toshiba’s baseball team lend their skills to solving the problem

Fortunately, the skies didn’t open and the experiments were done. A hitter positioned under a lighting tower whacked balls high into the air to be caught by the five players. They were arranged to view the ball from different angles, in four hitting patterns, which realized 20 ways of checking whether or not the ball got lost in the lights.

The basic finding was clear: the ball disappeared when it passed in front of lights that were at a threshold luminance—and the larger this area of high luminance, the more likely the ball was to disappear. Armed with the results, he headed back to the lab to study the relationship between luminance and ball disappearance. The tests found an almost 100% probability of disappearance when the lighting was at an intensity of 300,000 cd/m 2 or more.

Higashi and Hata at work in the lab

Though the experiment was tough to set up, the results were worthwhile. Working directly with the players in on-field experiments generated a lot of insights.

“Normally lighting experiments are confined to the lab, and we only venture outdoors if we need to confirm something,” explains Higashi. “This time, though, I took the advice of my boss and did the outdoor experiment first. This was a good move. It reminded me of the importance of going out into the field, talking to people, not just staying confined in the laboratory. It was also really useful to talk to players with a lot of experience of night games, who told us that they sometimes have the same problem with HID lamps, too. I tried to catch a ball or two myself, and I was amazed how easy it was to lose sight of it. That’s when I realized that the lighting conditions weren’t actually that great for the players.”

More LEDs, better stadium experiences

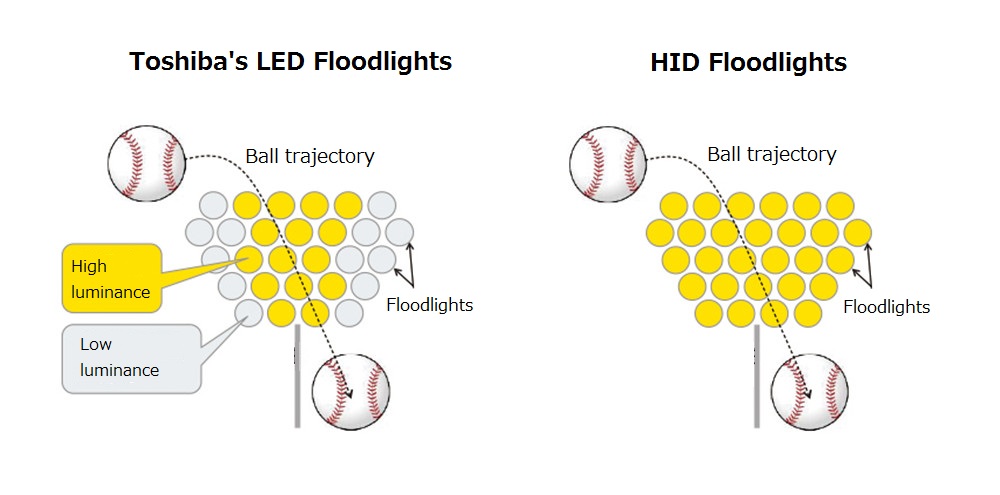

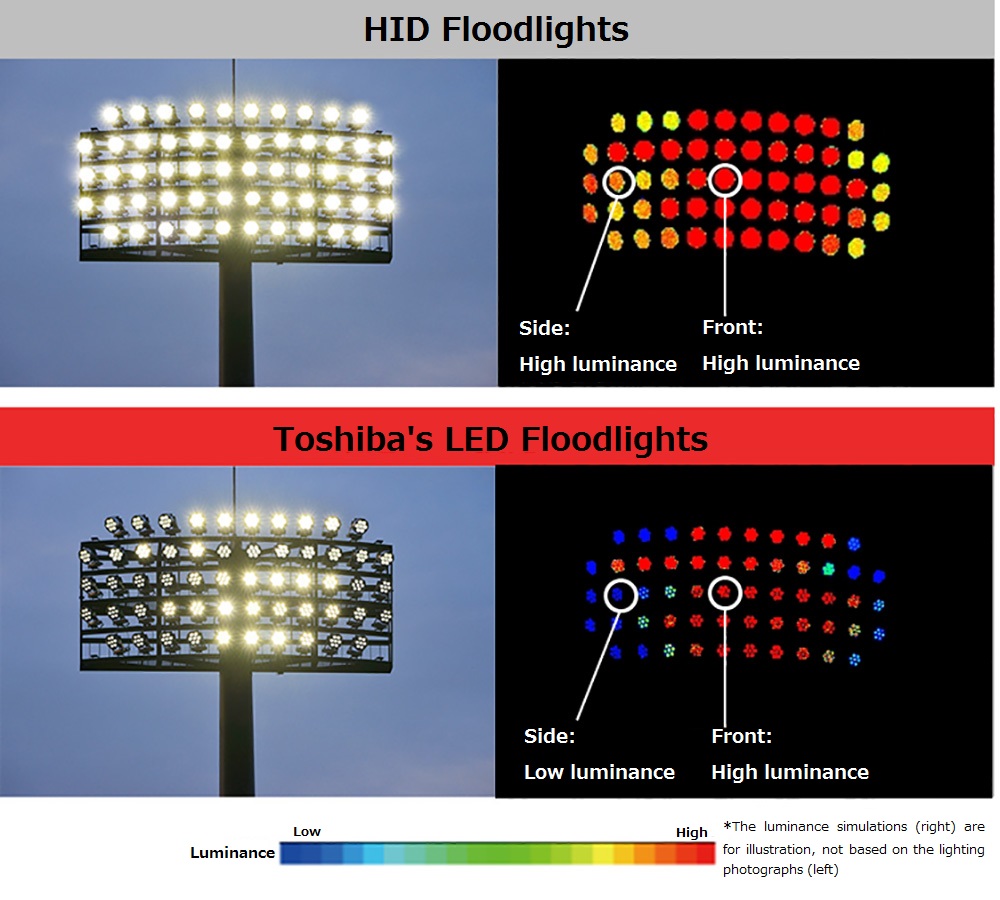

The most important thing about the experiment is that it also provided clues on how to design the lighting to reduce the ball disappearing phenomenon. The key lay in considering the luminance distribution across a bank of floodlights.

“In simple terms, you need to reduce the area of high luminance. LEDs are suitable for lighting baseball fields because their illumination is highly directional; not all the lights need to be set to have the same intensity as HID lighting does.The LED floodlight set-up that we have designed ensures that light remains tightly focused on targeted areas. By preventing light from leaking into adjacent spots, this improved design could provide an efficient lighting solution while also significantly reducing the problem of the ball disappearing in the lights,” Higashi explains.

This becomes obvious when we compare HID floodlight set-ups with LED floodlight set-ups. With more controlled distribution of luminous intensity, the LED bank appears significantly less bright when viewed from the side, but it lights the field and playing area just as well.

During the experiment, the players commented that “it felt like LEDs on the side of the floodlight were not even turned on.” This suggests that explaining the mechanism needs more understanding, but the experiment itself helped to figure out a better solution for baseball and other games that involve balls flying up in the air. The results of the experiments also confirm that LEDs can illuminate entire stadiums.

Hata, who works in the Technology Development & Quality Assurance Division, explains the quality of lighting. “LEDs are highly directional, and there were some concerns that they could only spotlight a limited space and not the entire stadium. We investigated this with more indoor experiments and studied whether highly directional LED floodlights could illuminate an entire baseball field. We found that setting the lighting at a certain level of illuminance would not cause any problem for catchers. We are confident that the current LED floodlight setting delivers illuminance that causes no problems for fielders catching balls.”

Yuki Hata explains her results

The results of the on-field testing and player-oriented research is used to improve the design of lighting for sports stadiums. LEDs are also capable of delivering vibrant greens and dynamic plays, and various lighting effects. Research into this technology is likely to make watching sports an even more thrilling experience.

Higashi and Hata, solving lighting problems one by one

![]()