Can ergonomics lead to greater well-being? -Ecosystems that go beyond mere comfort to support the synergistic cycle of well-being

2023/11/15 Toshiba Clip Team

- Ergonomics goes beyond manufacturing to interactions with products, environments, systems and services.

- Business and design groups collaborate in human-centric product and service design.

- The essence of ergonomics is the circulation of happiness.

When we buy a chair, we weigh our options carefullyーbecause we all know how important a comfortable chair is for our day-to-day quality of life. The same goes for a computer mouse; we want one that is easy to hold and use. The more we use something on a daily basis, the more care we take when selecting it. And products like these are meticulously designed with the user in mind. That’s where ergonomics comes into play.

Although the term is mainly used in connection with manufactured things, ergonomics has a wider realm that extends to solving everyday problems and making work and life easier. So what can it contribute to improved quality of life, and how? To find out more, we spoke to Kenji Ido and Shihomi Takahashi, both experts in ergonomics at Toshiba’s Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) x Design Division, which is responsible for creating products, services and interface designs that sustain continued progress in cyber-physical systems.

Ergonomics is more than ease of use—it’s about designing relationships with people

“The prevailing view is that for more people to benefit from technological advances, we need to design goods and services that better accommodate their needs,” says Ido “This is human-centered design, and our understanding of its role has expanded over time.” He speaks with the knowledge and familiarity of someone long immersed in the subject, which he also teaches at university.

Kenji Ido, Fellow, Design Management Office, Cyber-Physical Systems x Design Div., Toshiba Corporation

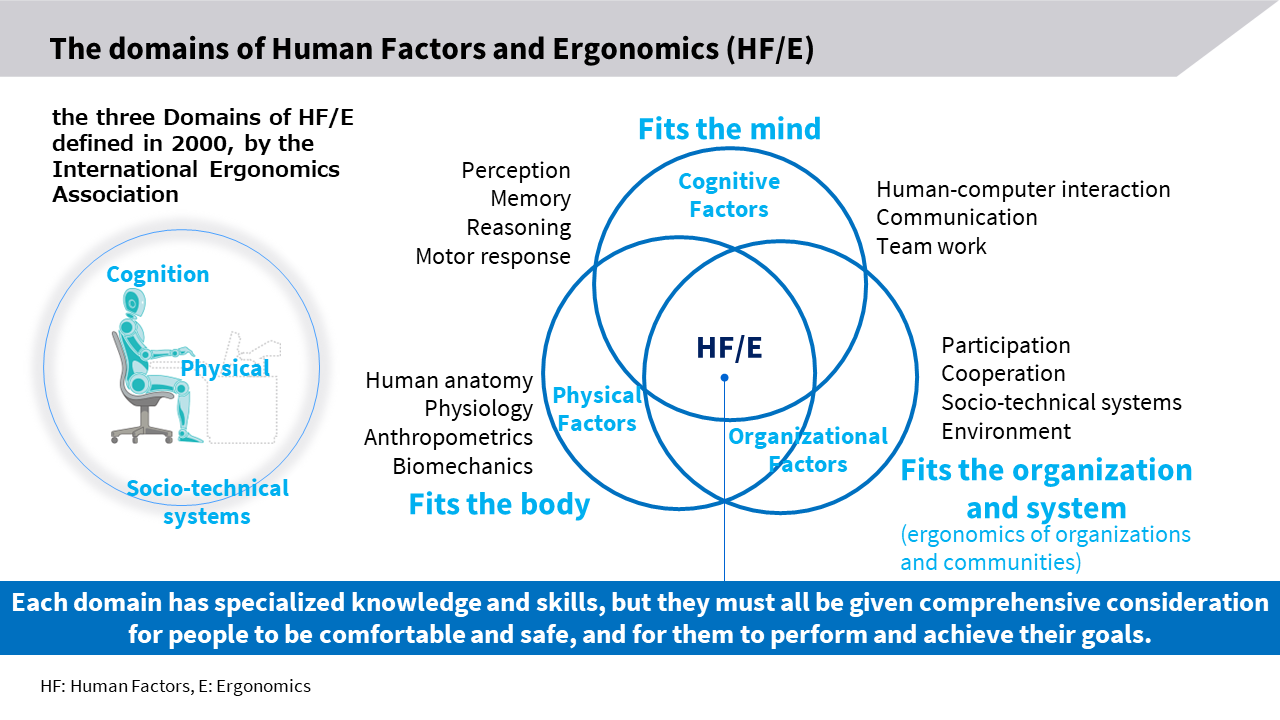

“Ergonomics has all sorts of applications in many different fields,” says Ido. “The compatibility of products like chairs and mice with our bodies is an important factor, known as physical ergonomics. But it is only a small part of the story. We also have cognitive ergonomics, which is concerned with designing things that conform with our cognition, the way we mentally engage with things, such as devices that are easy to operate and screens that are simple to navigate.

Then we have organizational ergonomics, which relates to the design of organizations and sociotechnical systems. Examples here include work shifts that are easy for people to work and that improve performance, compensation systems that raise motivation, and making people feel at ease and comfortable in organizations. Ergonomics is broad, and covers the design of our relationships with things; between people and manmade objects, and with the environment.”

Graphic adapted from the three “Domains of HF/E” defined by the International Ergonomics Association.

Each domain has specialized knowledge and skills, but they must all be given comprehensive consideration for people to be comfortable and safe, and for them to perform and achieve their goals.

Shihomi Takahashi researches design psychology. Her specialty is cognitive ergonomics, understanding factors like “respondability” and “memorability,” and she sees a crucial role for ergonomics in this age of digital technology and AI.

“Design psychology is looking for a scientific understanding of how we think about and react to goods and services. With digital products and services it is much more difficult for us to get a good idea of internal mechanisms, how things work under the surface, and we need to design them with operational methods and user interfaces that conform with the expectations of human psychology and cognitive characteristics.

“Advances in technology now allow us to visualize brain activity, so we can conduct even more detailed psychological analyses. As technology evolves and spreads, the domains covered by ergonomics continue to expand.”

Shihomi Takahashi, Specialist, User Interface Design Group, Design Development Department, Cyber-Physical Systems x Design Div., Toshiba Corporation

Ergonomics is essentially a child of the Industrial Revolution in Europe, and it has developed hand-in-hand with advances in industrial technology. In Japan, it started to attract widespread attention in the 1990s.

“Mass production and consumption reached their peak during Japan’s period of rapid economic growth,” says Ido. “People consumed more and more products and services that were often designed with little thought for people’s physical or cognitive characteristics. Later, as Japanese society matured, from around 1990 on, for products and services to sell well, they had to be easy for anyone to use, or have what is called human-centered design. This is when ergonomics came into its own.”

Ergonomics came into its own at the transition from a time when people adapted themselves to goods to one where design stepped in to ensure goods adapted to people. As Ido asserts, “As long as people are involved, ergonomics applies to all goods, services, and systems.” Among these, one area gaining prominence is ergonomically based human-centric manufacturing.

All products and services start with thinking about people

The CPS x Design Division collaborates with Toshiba’s business units in projects. Through internal and external collaboration and co-creation, it is helping to promote manufacturing that embodies ergonomic concepts.

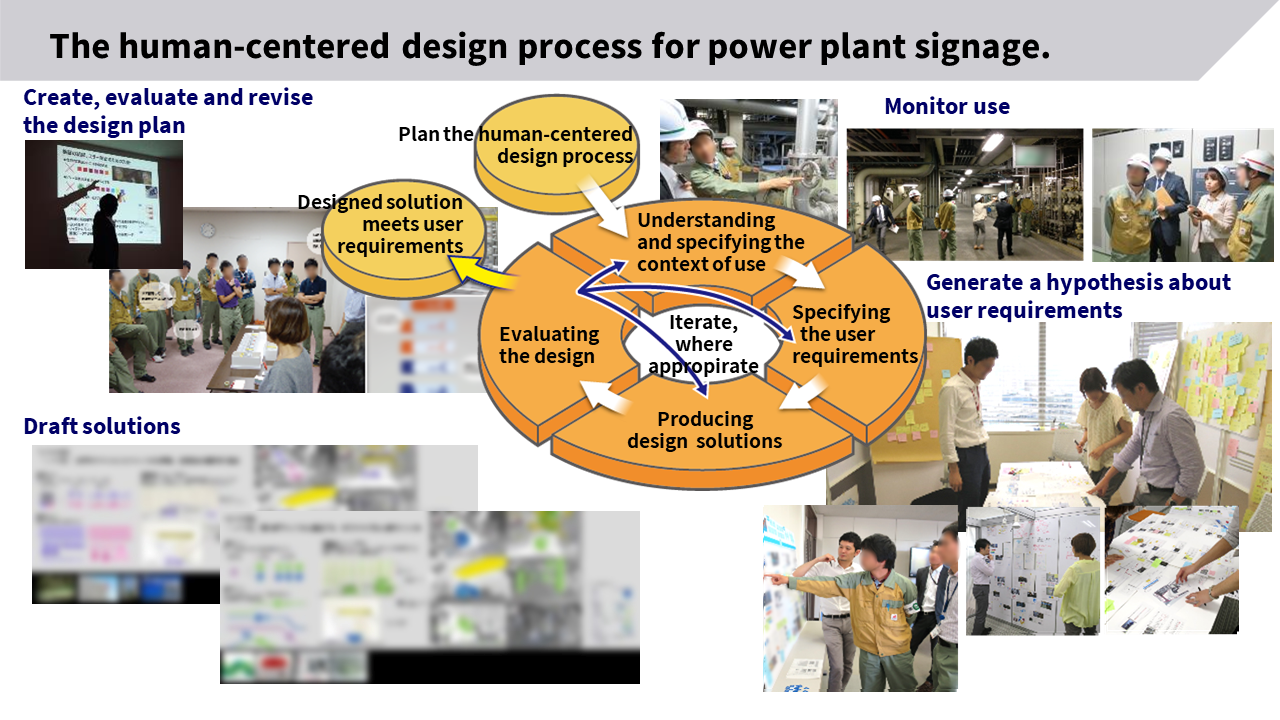

As we have seen, there is much more to design than just making things look beautiful. At Toshiba, the creative process begins with ergonomics, by seeking to understand users. Take, for instance, the design of a signage system for a power station commissioned in 2018.

Nishi-Nagoya Thermal Power Station Group No. 7, where ergonomics was used to design the indoor sign system

Nishi-Nagoya Thermal Power Station Group No. 7 installed a new power generation system that emits 1.4 million metric tons less CO2 than the older equivalent equipment it replaced. A Toshiba design team worked on the interior signage system for the upgraded facility.

The design incorporates an innovative color scheme of white, blue and lemon yellow that gives primary consideration to the people who maintain the equipment. This rethinking of how people interact with power generation facilities and their equipment won the signage project a Good Design Award.

“Our first priority was to prevent human error,” says Ido. “The plant is vast, with many similar-looking systems, which raised concerns that workers could misidentify them and the equipment to be inspected and maintained. We countered this by bringing our knowledge of ergonomics to the signage system.

“With the need for human-centric design at the front of our thinking, we worked with the business unit to really understand daily routines in the plant. We then identified latent needs, where people say things like, ‘I wish it were more like this,’ and drafted solutions and incorporated them into the design. After that, we got the plant workers to evaluate what we had done, and used the feedback for repeated fine tuning.”

It was not only the reduction of potential for human error in the inspection and maintenance of the facilities that made Ido happy.

“As our designers visualized the issues and needs, the customer had the pleasure of seeing things they had talked about take shape, and this strengthened our ability to create together. We also started to hear comments like, ‘I feel more motivated to work here.’ For designers like us, the great thing is to draw out needs that are only really understood by people on site, and to hook into their energy. A creative process that incorporates the requirements and passions of users and organizations—that’s the essence of ergonomics.“

Carefully address customer requirements and incorporate them into the design by conducting surveys, defining user requirements, drafting solutions, and evaluating results.

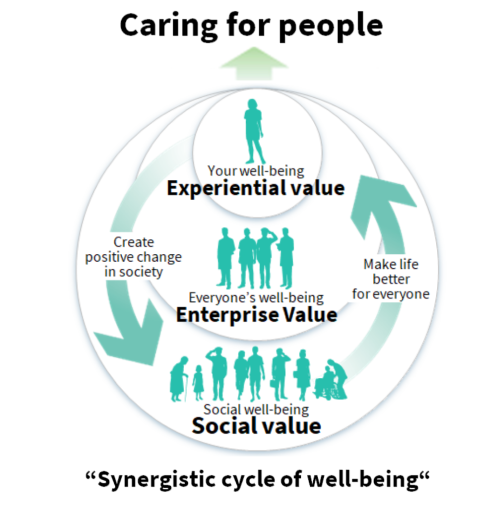

The goal of ergonomics is the creation of ecosystems that support the circulation of happiness

This example of implementing ergonomics is grounded in the concept of human-centered design. The keywords that Ido uses to convey this are “the synergistic cycle of well-being,” and he explains what that means in the real world: “Workers at the plant where we designed the signage told us they were proud to work there. This positive attitude improves organizational strength, and safe and stable operation of the organization and plant also benefits the local community. The future of ergonomics is to aim to go beyond local design, to create systems that have a positive impact on society and organizations as a whole. What this means is that circulation of happiness realized by human-centered design is an ecosystem that affects everyone involved.”

Human-centric design of products and services embodies the synergistic cycle of well-being

Takahashi also has views on the future of ergonomics, based on history and current conditions. “The Industrial Revolution marked a major milestone, and today too we are at a new turning point, characterized by growing uncertainty and increasingly diverse and complex needs. When the things people demand change, the environment changes with them, and new technologies are adopted to meet those needs.

“As times change, the way ‘usability’ people perceive also changes, this is why we need to pursue technologies and systems that fit to society from the perspective of ergonomics. In this sense, ergonomics is also about knowing human history.

“I am responsible for interface design for apps and websites. To get a real understanding of the underlying issues and needs, and to create real value, I want to work continually with business divisions, rather than just participating here and there in the process.”

While Ido and Takahashi agree that it is important that people feel comfortable, when they use a service, they also believe that the experience must meet latent needs, so users say, ‘Yes, yes, this is what I wanted.’ They also believe that keeping up to date is a must, to make use of new technologies.

Ido is emphatic about how important this is: “I want to see everybody in the design department able to promote the synergistic cycle of well-being concept through human-centered design. To this end, my focus is on training the next generation by introducing the concepts of ergonomics and case studies, both inside and outside the company.

“But this is not limited to design. Let’s say there’s a point in a supply chain for a product or service that makes people happy that is under strain. That kind of design cannot last, and its failure will stop the circulation of happiness. Toshiba Group’s basic commitment is ‘Committed to People, Committed to the Future.’ And what we need to aim for is the creation of systems that brings happiness to our employees, our customers and partners, to everyone.”

The synergistic cycle of well-being starts with people and ends with people. It is a constant sequence of events that exits to put smiles on people’s faces.

![]()