Decommissioning Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Young Engineers Take on Unknown Challenges

2024/01/10 Toshiba Clip Team

- Decommissioning Fukushima Daiichi, a project expected to take 30 to 40 years

- Getting the full picture on fuel debris to retrieve it. The route to equipment development

- Positive young engineers take the lead in a long-term project

March 11, 2011… The Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami trigger a major accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. They also initiate a quiet struggle by engineers, steady efforts to decommission the plant that continue to this day. The struggle will be long and arduous, a daunting project that is expected to last another 30 to 40 years—but the engineers we interviewed for this article are forward-looking and confident. “All of our efforts will be world-firsts,” they say, and their positive approach to is sure to make a difference.

In this article we take a closer look at the story, at how the people involved in the Toshiba decommissioning project have overcome obstacles, one after another, and what they see for the future.

A Team of Young Engineers Working as One—The Challenges of the Decommissioning

“One idea was for tongs like those used with pasta,” says Tessai Sugiura, a mechanical engineer at Toshiba’s Isogo Nuclear Engineering Center. “There was also the suggestion of shooting a metal ball, like the asteroid probe Hayabusa 2, which was in the news at the time. After getting a lot of opinions, we found our baby in ice tongs, because they grip ice without letting it slip. The idea for that came to someone at the center, who saw a set while shopping, and we developed a plan with that mechanism for handling objects.”

Tessai Sugiura, Third Mechanical System Design & Engineering Group, Mechanical System Design & Engineering Department, Isogo Nuclear Engineering Center, Toshiba Energy Systems & Solutions Corporation

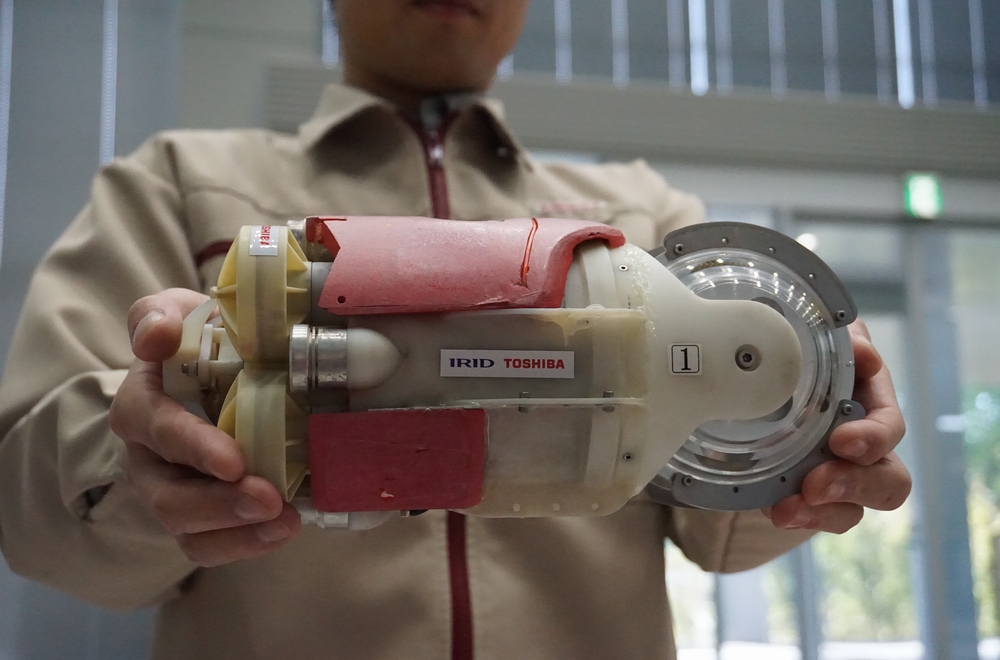

Even before the interview started, Sugiura immediately started to talk about the team’s baby, the deposits contact survey equipment he and his colleagues developed. In February 2019, it was this ‘baby,’ with fingers modeled on ice tongs, that entered and explored the interior of the primary containment vessel, the PCV, of Fukushima Daiichi’s Unit 2 reactor. Once there, it became the first robot to grasp and lift fragments of what looked like fuel debris.

The deposits investigation devices picks up fuel debris inside Unit 2’s PCV

Demonstrating the ability to pick up what is thought to be fuel debris is a major breakthrough, of crucial importance. Why? Because on March 11, 2011, the intense heat inside the reactor pressure vessels of Fukushima Units 1-3 caused reactor meltdowns that saw their fuel liquify and fall to the bottom of the vessels. Once there, it mixed with other substances and solidified as fuel debris. There is estimated to be over 800 tons of it.

Takayuki Nakahara was at Fukushima when the disaster struck, and has still vivid memories of the tense situation. He has led the PCV internal inspection team in the project to stabilize the plant since immediately after the accident, and has no doubts as to the scale of the problem: “The reason why the decommissioning project is seen as one of the world’s most difficult undertakings is the existence of the fuel debris,” he says.

“Radiation levels inside the PCV are far too high to allow people to get close,” explains Nakahara. “The hole through which we pass survey equipment into the interior is not large, and it is difficult to get far inside. It is also difficult to get an understanding of how things have changed inside the reactor since the earthquake. With all this, toward recovering the fuel debris, we had to carry out a detailed investigation of the internal conditions and confirm whether or not the deposits could be moved.

Takayuki Nakahara, Manager, Third Project Engineering Group, Fukushima Restoration & Fuel Cycle Project Engineering Dept., Power Systems Div., Toshiba Energy Systems & Solutions Corporation

“The development and operation of survey equipment cannot be handled with plans drawn up at a desk. Working on the project has made me keenly aware of the essence of on-the-spot decision-making. I was in my second year with the company when I started to work in the field. I was in a position where I had to give instructions to on-site workers, but at first I didn’t know my left hand from my right. There were things that I thought were good but that turned out to be unnecessary on site, and other things that I saw as unimportant were important out in the field. I had to handle a lot of unexpected events.

“I also learned that it is necessary to give people the right instructions, quickly and accurately, so they feel at ease in their activities. Work sites are scenes of constant change. The longer something takes, the more it costs, of course, and at Fukushima there is also the safety hazard of working for long hours in a highly radioactive area. On top of everything else, I had to interact with people swathed in protective clothing, so we had to speak loudly as we worked. For any onlooker, it might have looked like a shouting match, but by doing this we gradually built relationships of trust.”

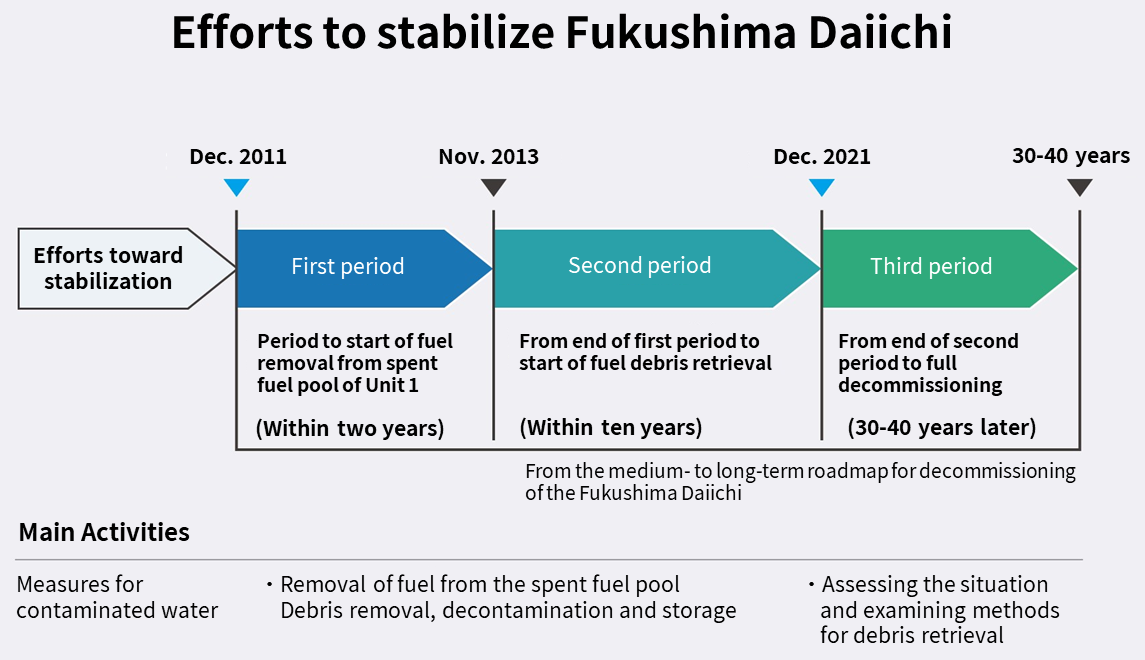

The government’s medium- to long-term roadmap for the decommissioning of Fukushima estimates that it will take 30 to 40 years, and we are now at the point of starting to move forward with removing fuel debris in the PCV. Toshiba has been involved in the nuclear power business since the 1960s, in the spheres of construction, maintenance and plant safety, and the company brings this knowledge base to the decommissioning process.

Several steps are required to complete decommissioning

“We have been working on measures to deal with contaminated water, fuel removal, and to investigate fuel debris in the PCV,” says Nakahara, returning to his team’s efforts to remove the debris. “Our top priority is safety. With limited time available onsite for investigations, if we can shorten each operation by even 10 seconds, it will help to make work safer and more reliable. We make detailed preparations to ensure safe operations, including detailed simulations using a model of the facility.”

The reality of an unprecedented challenge, where everything is a world first

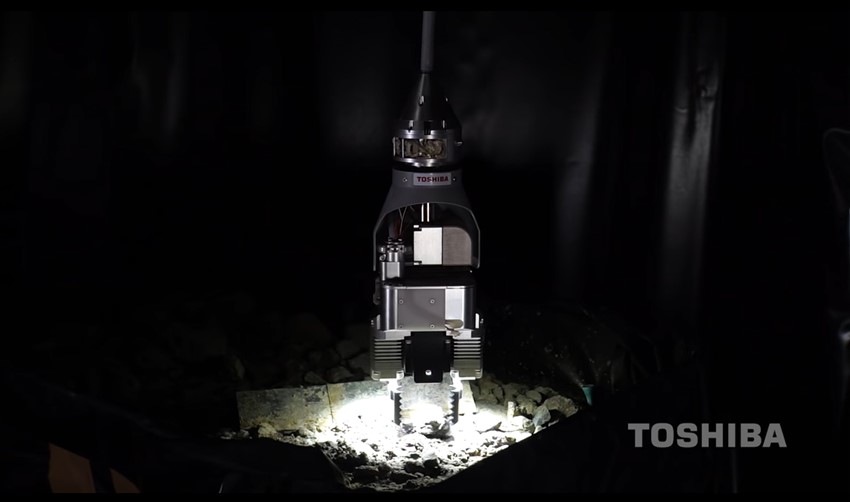

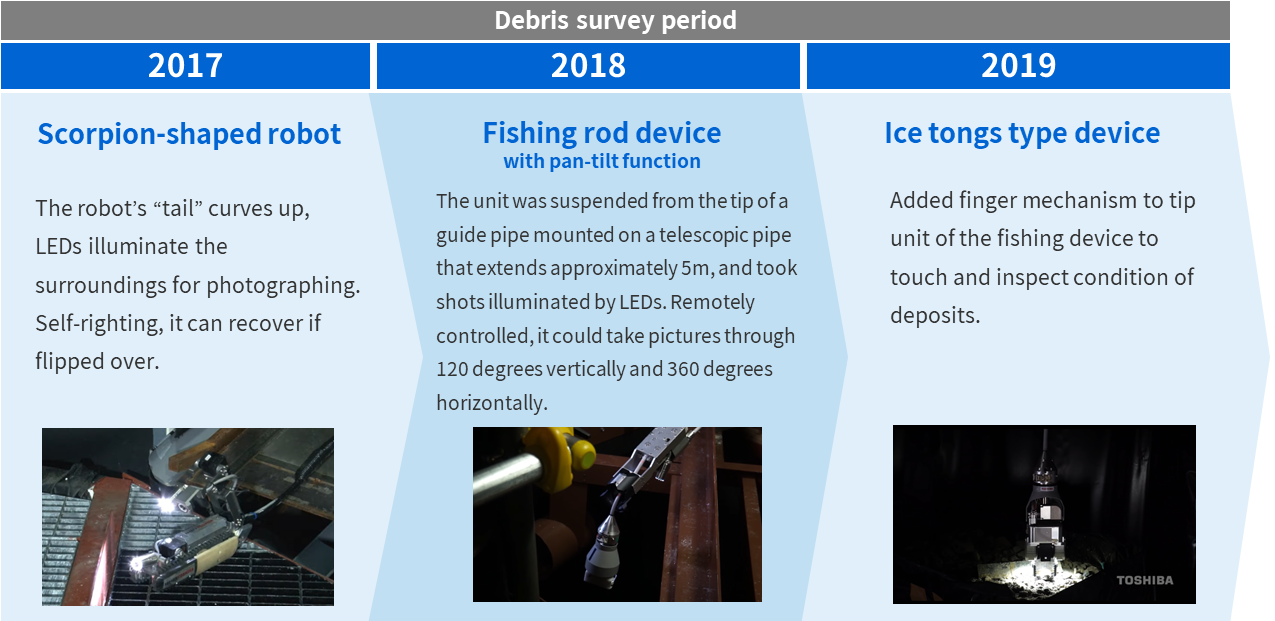

The first generation was a “scorpion-shaped robot,” the second a “fishing rod,” and the third the “ice tongs.” In 2017, the scorpion-shaped self-propelled survey device, equipped with a light on its tail, was the first robot to enter the PCV. A year later, deployment of the fishing-rod, a survey device with a camera suspended from the end of a fishing-rod-like pole, captured the first photographs of the bottom of the PCV. In 2019, the survey equipment that Sugiura affectionately calls “their baby,” grabbed the first deposits of what is believed to be fuel debris, securing a foothold for its eventual retrieval.

Sugiura explained how they try to get the most out of the technology they have developed. “Areas exposed to strong light appear washed out and blurry, so for the second-generation fishing-rod, we devised a way to move the camera and lighting away from each other once it had passed through the narrow entrance and before reaching the inside of the PCV. In 2019, we converted the motor mechanism that puts distance between the camera and the lighting and used it in the third-generation device to grab the deposits.”

In fact, dedication and repeated trial and error won improvement in survey functions in each generation of devices. The pipes used to move survey equipment into the PCV were elongated to the extent possible, and the cameras on devices made as small as possible. Specialized departments working on parts carried out repeated studies on the devices deployed, from the scorpion-shaped robot to the fishing rod device and the ice tongs, to improve their size and survey functions.

During the development process, improvements have been made using on-site knowledge

Nakahara understands the unprecedented nature of the situation. “Every aspect of decommissioning we are involved in carries the label ‘world first,’” he says. And among companies involved in the work, Toshiba is alone in having people in their 20s and 30s as leaders. With no previous cases to refer to, these young engineers are taking on problems nobody has ever faced before.

“At Toshiba, young people who recently joined the company are often selected to lead projects,” says Nakahara. “Take Mr. Sugiura, he was tasked with improving the equipment and coordinating its installation at the site. There are also skilled engineers who provide solid technical support in the background. We carefully convey the knowhow Toshiba has cultivated in the nuclear power business; things about the internal structure of the reactor that cannot be seen in design drawings, and the knowledge gained from refurbishing the reactor. The project is being carried forward by a good fusion of young people who are energetically moving forward with a vision of the future plus skilled engineers with valuable experience.”

Workers in protective clothing at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant

From decommissioning, on to the next generation—looking ahead, connecting technology and ideas

The decommissioning schedule is clear in its intent, and says that the fuel debris retrieval Nakahara and his team are working on ‘will start with trial retrieval from Unit 2 and be scaled up in stages.’ Nakahara will be in charge of Toshiba’s contributions to the overall decommissioning project, while Sugiura is working on a system to monitor the interior of the PCV.

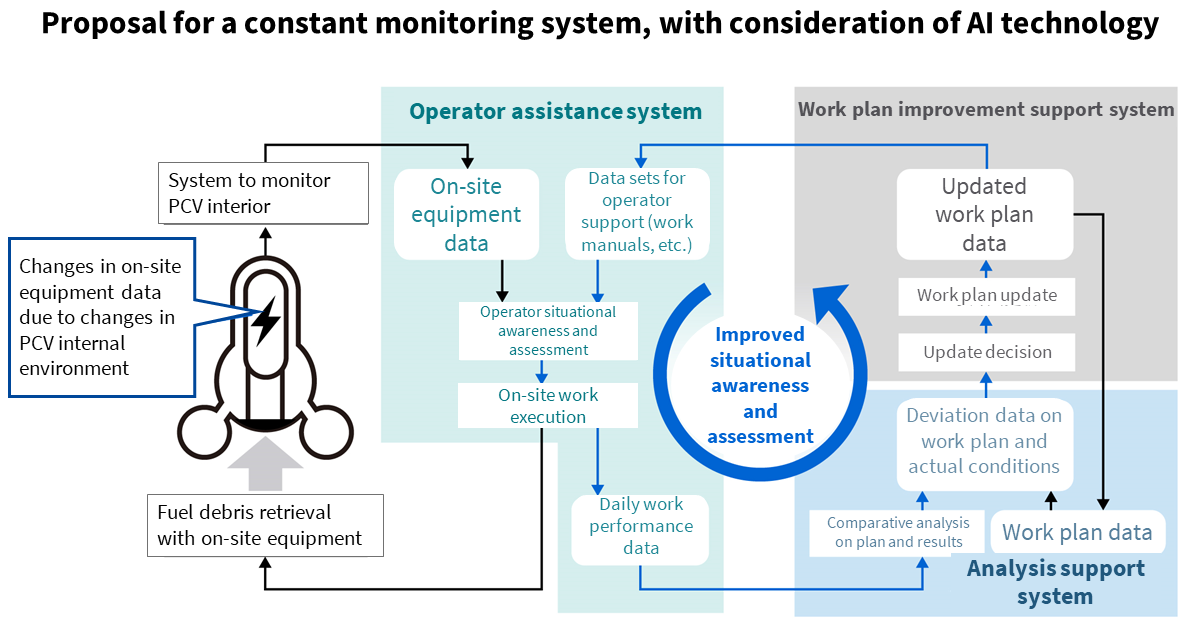

“Once we know what is going at the site, we will know how we can safely retrieve the fuel debris” says Sugiura. “We are developing a monitoring system to support this. After all, it is people who operate the equipment and are involved in its maintenance, and if the system cannot be used on site, there is no point in developing it. For example, about 200 items to monitor have been listed as required for the retrieval of the fuel debris, such as radiation levels and temperature, but not all of those can be deployed on site as they are now.”

“This is where the power of digital technology comes into play,” says Sugiura. “Extracting meaningful information from large volumes of data needs a system that can process the data with cyber support tools like, for example, Explainable AI, and make quick and accurate judgments about the on-site situation. That’s the kind of system we are developing, while being fully aware of on-site thinking based on our investigations of the PCV interior. Moving forward, I want to advance the development phase through a thorough dialogue with people in the field.”

Working out how to utilize AI and monitor PCV data to support fast, accurate operator responses

“This concept really is the essence of cyber-physical systems,” observes Nakahara. “CPS collects and analyzes data from sources like manufacturing sites and returns it as valuable information. Although this is our first initiative, the power of digital technology is making a significant contribution to the decommissioning. In addition to the data analysis, we will contribute to the decommissioning by integrating the on-site knowledge we have accumulated in our work with Toshiba’s experience in nuclear power projects.”

Although we are beginning to get a vague grasp of the situation, there is a growing number of unknown areas inside the PCV. Barriers that we cannot see yet will undoubtably loom large in the future. In circumstances like these, and in this long, long project, how do the engineers feel about what they are doing?

“Ever since I was a kid, I always wanted to be a robot researcher,” says Sugiura. “I had a friend who was from Fukushima, so the disaster was not just something that happened to someone else, and I volunteered to work at the plant. Now, while involved in the development of research equipment, I can also do my best for Fukushima. If I can help people by doing what I want to do, there is nothing more that I can hope for. Someone has to do it, and I am proud to be a part of the effort.

“I wanted to work on the construction of nuclear power plants – that’s what I had in mind when I joined Toshiba, and shortly after that the earthquake happened,” says Nakahara. “I want to dedicate my life to cleaning up the nuclear power plant and regaining the trust of the public. Younger workers like Mr. Sugiura are getting experience in the field. By the time they really hit their stride as engineers, they may find an even bigger project waiting for them. I hope that we can pass on awareness and insights gained from working on the site to the next generation.

Removing the fuel debris is only one part of this far-reaching project. The road ahead is long, but the team has a positive attitude and cheerfulness that seems to defy the circumstances. “It makes me happy to see something I worked on take shape, and then to see it working and helping us to advance step by step. I want to enjoy what we do without any sense of gloom,” said Nakahara. This is the pride he absorbed from watching his seniors who were on site at the time of the earthquake. His brightness is imbued both with calm and a solid determination to create a better future. The tunnel is long but there is light at the end. After the end of the countless efforts of the team, we can hope for a future for Fukushima, and for a brighter society.

![]()