Superconducting Motors are on the Flight Path to Carbon Neutral Planes, Part2 -The next step is to fly with them

2023/04/19 Toshiba Clip Team

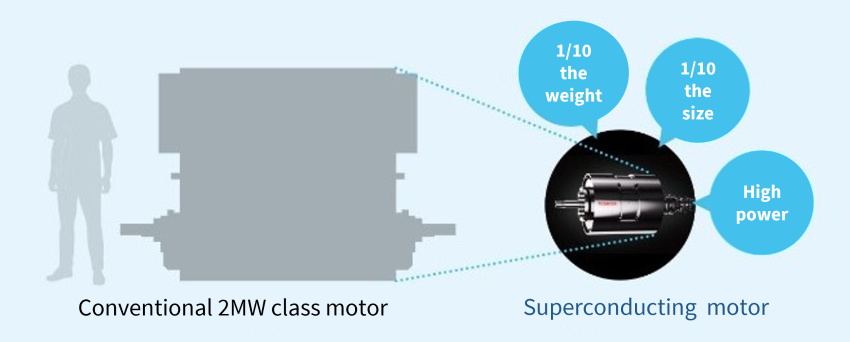

- Compact, less than 1/10 the weight of conventional motors, but with the same output.

- Seeing technology in terms of social issues. Why Toshiba developed a superconducting motor.

- A culture of "Everyone is equal in the face of technology," and pursuit of a shared goal.

The aviation industry aims to reduce CO₂ emissions from international flights by 15% from 2024 on, benchmarked against 2019, and to cut them to net zero by 2050. In Part 1 of this two-part article we reported on how Toshiba has responded to this target by completing the world’s very first light, compact, high-power superconducting motor, toward using electric energy to fly aircraft instead of fossil-fuel energy.

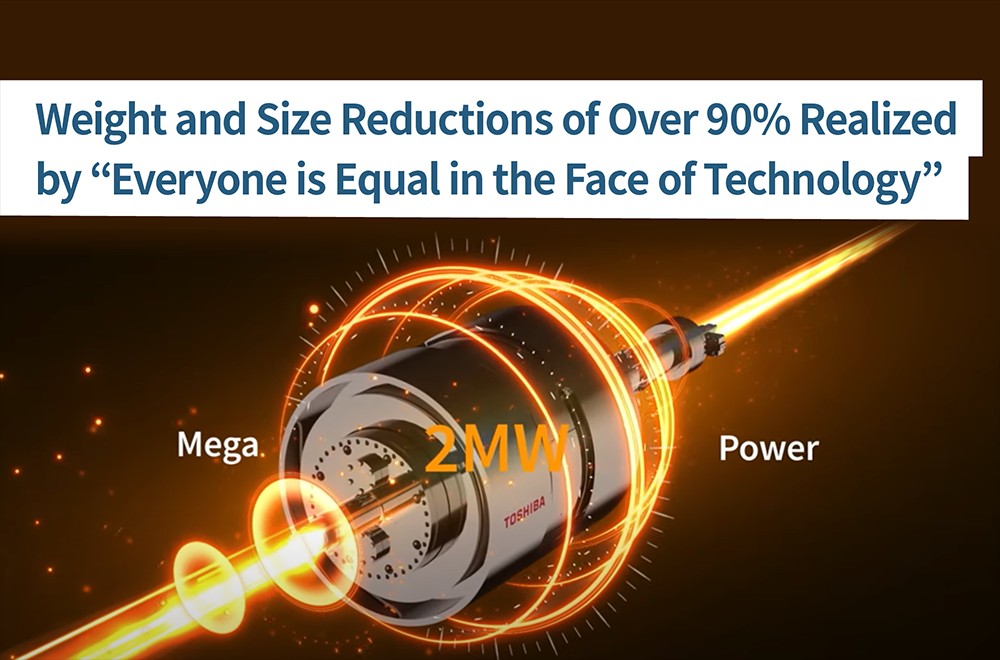

With the elimination of fossil fuel as their ultimate goal, companies around the world are vying with one another to avoid missing out on the development of next-generation aircraft. From research institutes to venture companies, competition to develop a superconducting motor as the core component for these aircraft is intense—but so far, none of them have successfully developed a light, compact motor that achieves the required output, 2 MW, and that can mounted on an aircraft.

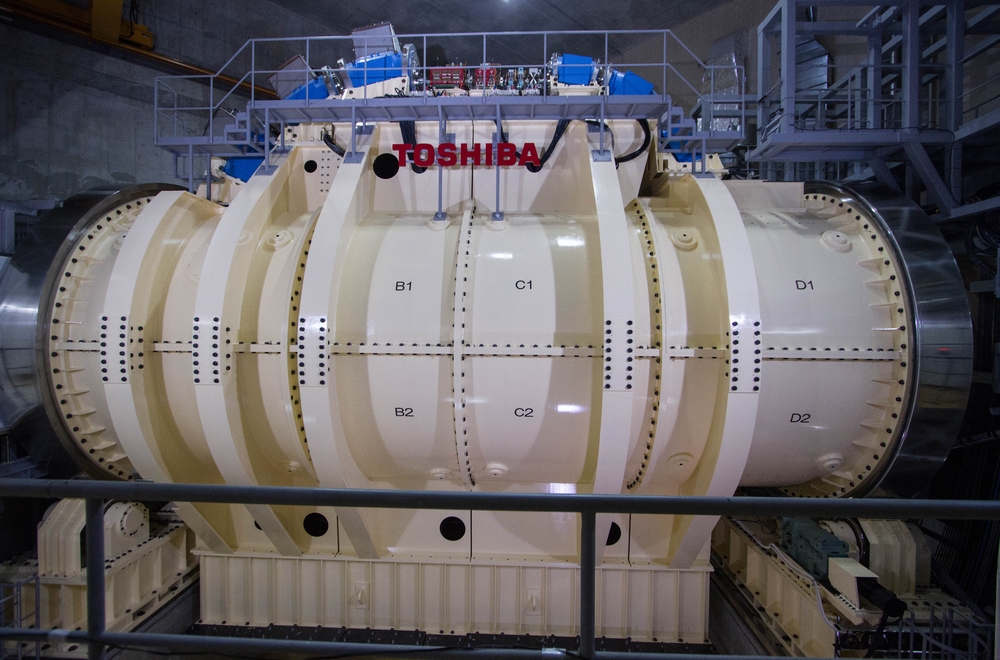

Against this background, a motor weighing only a few hundred kilograms, with an outer diameter of only some 50cm and an overall length of about 70cm (shaft excluded), only 1/10 that of a conventional motor with the same output, has been developed by Toshiba, and it is attracting a lot of attention both in Japan and overseas. Realization of this world-first motor owes everything to the hard work and determination of the people who worked on it, and in this second part of this article we talk to some of the young engineers who played a part.

Less than 1/10th the weight and size of other 2MW-class motors with the same rated output

A determination to solve a global social issue

As Tomoyuki Takahashi of Toshiba Energy Systems speaks, a smile plays across his face. “At first, I really wondered if it was possible to cut the weight and size to less than a tenth of a conventional motor. And then, to get the output we needed, we had to make it superconductive and achieve high speed rotation…” Takahashi came to the project from the design of turbine generators, and was assigned to work on all aspects of the motor’s design and testing. In simple terms, superconductivity means securing zero electrical resistance, to maximize electron flows.

Tomoyuki Takahashi, Turbine Generator Design Group, Design Dept.2, Keihin Product Operations,

Power Systems Div., Toshiba Energy Systems & Solutions Corporation

Takahashi recalled that, about 25 years ago, Toshiba had worked on development of superconducting power generators. He thought about it—maybe there was something there that could be applied to superconducting motors. He carefully read through the old materials, but he found a lot of differences in the scale and mechanisms of generators and of motors for mobility applications, and realized there were many new things to consider. It all led him back to his original question: “Is this really possible?”

However, Takahashi did not give up.

“We thoroughly investigated all sorts of variables to see what we could do to get the weight and size down,” he says. “We looked at the details and asked ourselves things like, ‘What would it do to the weight if we made this thickness progressively thinner?’

“Another thing we asked was, ‘Would changing one part affect other parts, so that the motor becomes unviable?’ and we ran all the simulations we could think of. We used know-how from other project team members, and also from other departments. We spent a lot of time on this project, and that allowed us to improve the reliability of the equipment.”

After much trial and error, the team arrived at a basic design for a superconducting motor that met the size and weight criteria. We asked Mr. Takahashi where the team found the determination to take on a challenge that demanded such precision, to reach a goal never achieved before.

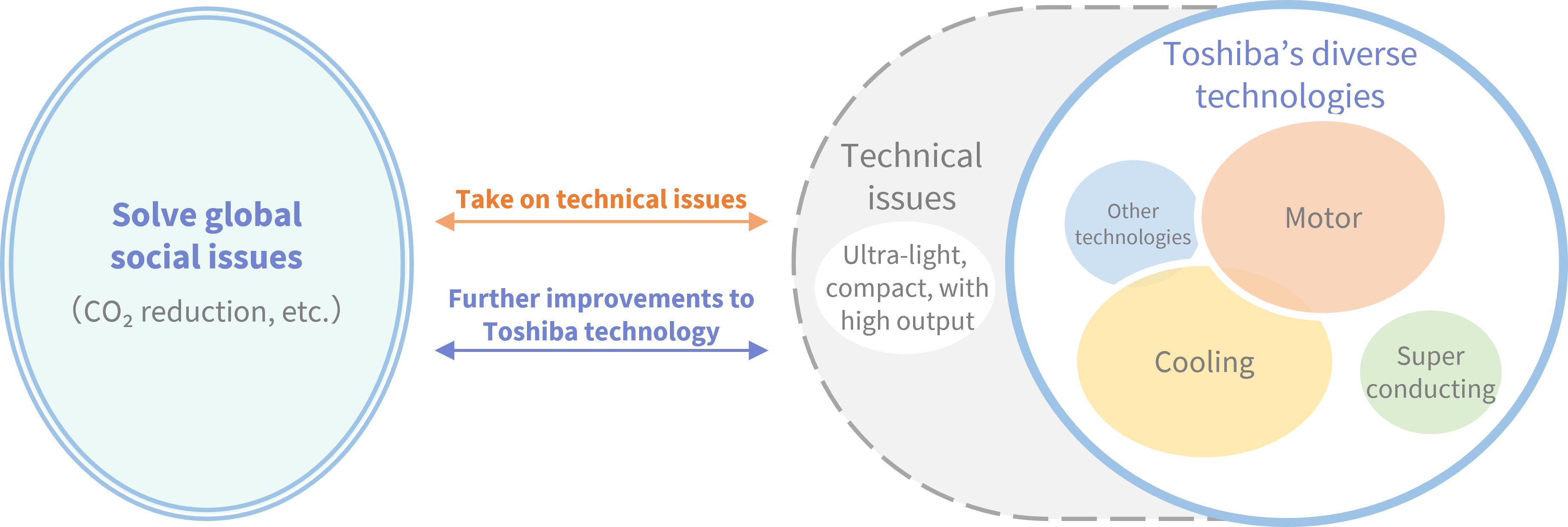

He answers naturally. “I think Toshiba’s ethos is to use its technological capabilities to solve social issues on a global scale. The Toshiba way isn’t to say ‘we can do with this weight and size,’ but ‘this is the weight and size necessary to solve the problem.’ I think that level of determination led to this world-first success.”

The creation of electric aircraft is focused on overcoming a global social issue and advancing carbon neutrality. Takahashi’s response shows that he is aware of this and sees it as the natural thing to do. In fact, while they do not generally talk about it as in issue they must tackle, it is apparent that the other team members share this recognition, and understand Toshiba’s role as a provider of social infrastructure products and services.

Identify technological issues linked to solving social issues and improve the technology

At Toshiba, age does not matter: everyone is equal in the face of technology

Like Takahashi, Keita Nakama also works for Toshiba Energy Systems & Solutions, but rather than basic turbine design, he is more focused on detail, in this case the design of the motor’s cooling mechanism. “Through this project,” he says, “I was again reminded that Toshiba has capable specialists in many areas.”

Keita Nakama, Specialist,

Turbine Generator Design Group, Design Dept.2, Keihin Product Operations,

Power Systems Div., Toshiba Energy Systems & Solutions Corporation

Nakama recounts the challenge he took on. “The only way to reach a superconducting state is to cool things down to a very low level, a cryogenic temperature, and to do that we had to design a cooling structure and flow path for the refrigerant. We had design and test data from past designs that we could use as a reference to help us predict what our design would achieve. Even though we had to make course corrections along the way, we were able to make the intended equipment.” However, that does not mean there were no uncertainties.

“The thing you have to remember is that this was a world first,” Nakama says. “That meant, naturally enough, that we had no hard data. Even when you come up with a design that looks good, you really don’t know if it will work as expected. I was quite nervous until we tested it in the superconducting motor.”

Nakama had to contend with a wide range of issues, including measures to prevent metal shrinkage at cryogenic temperatures, to maintain cryogenic conditions, and to ensure insulation from ambient heat. Finding solutions to these problems was made possible by the corporate culture and the wide ranging knowledge of Toshiba’s engineers, as he has noted.

“Even though we work at different sites, we keep in touch with each other when working on a required technology; I think this pushing forward toward the same goal is a distinctive part of Toshiba. There is this spirit that we are all equal in the face of technology. During discussions, if Mr. Takahashi or I think something our supervisor says is a little off the mark, we can just say so, and it isn’t unusual to see objections accepted. We can all say what we think to each other, and then unite to tackle issues. This is the great thing about Toshiba.”

A first-time experience for an engineer who uses “Why” as a tool to achieves a world first

Itaru Abe is younger than Takahashi and Nakama, in his third year with Toshiba. He works at Toshiba Energy Systems’ research and development center, and in the motor project he was responsible for the coil that conducts electricity to the rotor and brings it to a superconductive state.

Itaru Abe, Quantum Systems R&D Dept., Energy Systems Research and Development Center,

Toshiba Energy Systems & Solutions Corporation

Abe appreciates the workplace he has found at Toshiba. “Mr. Nakama mentioned how we are all equal when it comes to technology,” he says. “In addition to that, we don’t use honorific titles other than ‘san,’ whether it’s subordinates talking to superiors or vice versa, or even with the president of the company. That brings equality to discussions, and makes it easy to ask questions.

“When you handle superconductors, as I do, or are responsible for motors, like Mr. Takahashi and Mr. Nakama, your idea of what’s common sense can be the other person’s recipe for insanity. For instance, superconductors are usually used in a static position, but we had to build this one into a motor, which rotates. We had to consider rotational and centrifugal forces and other things we normally don’t think about.

“Because of this, I tried to communicate politely, and when I had to tell people things like, ‘Doing this is dangerous with superconductors,’ or ‘Please keep the values below this level,’ I tried to explain why by showing them numerical values.”

At university, Abe studied inorganic materials and magnets, and it was a surprise to hear that he started working on superconductivity only after joining Toshiba.

“This was the first time I worked on superconductivity,” he explains. “That gave me the chance to get to the bottom of what my seniors were saying, and to ask ‘Why is that so?’ From that, we got to various optimizations for rotating the superconductor, something that is not normally done.

“Whenever things did not going as expected during testing, I couldn’t just disassemble the motor; I had to use the data and stretch my imagination, and whenever I had a problem I listened to what my seniors said. I repeatedly thought and rethought problems through for myself, so I was able to overcome them even though I was working in uncharted territory.”

Spontaneously, in astonishment: “We’ve finally come this far!”

Toshiba announced the superconducting motor in June 2022. Interest was immediate, and inquires flowed in from aircraft and engine companies, from universities, and from other sectors, including mobility companies such as automobile and railroads companies. There is growing anticipation of commercialization in a number of industries. Many visitors who have seen the motor have expressed their surprise with comments like, ‘I didn’t think it would be this small,’ and ‘Has practical application of superconductivity really come this far?’

However, despite the great response to the motor, this is not yet a story of “happily-ever-after.” The motor is only the first prototype, and there are still issues to overcome. So we can conclude by once again hearing from the engineers interviewed in this story, and of how they are already looking ahead to the next challenges, and to future developments.

Takahashi: “To put the motor on an aircraft, we need to make it even lighter. We will confirm reliability for practical use in long-term tests, improve the materials and structure for mass production, and finalize the design with consideration for cost. The next model will be more challenging,” he says, envisioning the path to commercialization.

Nakama: “This time, we have verified the feasibility of a light, compact motor with high power output. There are still many issues to solve, including balancing the internal weight and reducing vibration from rotation. The real work starts here, and we will ensure reliability as a company responsible for social infrastructure,” he says emphatically.

Abe: “We will ensure that the motor does not break up, even at high rotation speeds, by defining strict standards for dimensions and weight, and we will use data to control quality. If this is difficult with materials, we will find structural solutions, and ensure reliability and safety for use in mobility, and also keep a close eye on quality.”

Toshiba’s management philosophy is summed up by “Committed to People, Committed to the Future. The challenge of embodying these principles in an electric aircraft powered by a superconducting motor continues.

Young engineers who contributed to the development of the superconducting motor

![]()